How to Navigate the Reservoirs of Cáceres

Portada » Archivo de c2o

Water management in Spain falls under the jurisdiction of the State. This authority has not been transferred to the Autonomous Communities because most river basins supply water to more than one of them. Water management is divided into nine River Basin Authorities, which operate as autonomous bodies.

The six main uses of water in Spain can be summarised as follows: supplying populations, agriculture, industry, energy production, aquaculture, and recreational activities. The Spanish Water Governance System was recently developed as a management plan for the coming years aligned with the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Spain has a reservoir capacity of approximately 56,000 hm³. Of this, 7,000 hm³ is located in our province (accounting for 13% of Spain’s total water supply), making it the second-largest in the country after Badajoz.

The province of Cáceres is supplied by the Tagus River Basin for the most part, with additional contributions from the Guadiana and Duero basins. This article will focus on the recreational uses of water, which account for virtually 0% of water consumption, as these activities are primarily water-based recreation. Other recreational uses, such as golf courses and ski resorts, are not significant in our province.

Recreational Use is legally regulated just like any other water use, which is why it is necessary to obtain a permit whenever water is to be used for: 1) navigation activities, and/or 2) the installation of navigation infrastructures such as buoys, access ramps, cables, or docks.

The procedure itself is not complex, but there is no question that the administration needs to be more efficient in handling applications and processing fees.

Types of watercraft that require a permit

First of all, jet skis are not permitted (except on the Alcorlo Reservoir).

The maximum length is 9 metres for sailboats and rowboats, and 7 metres for motorboats. The maximum engine power is 240 HP, and only 4-stroke gasoline combustion engines are permitted.

What you need to do before you set sail

The first thing is to file a Statement of Compliance in order to obtain a permit for the recreational use of water. It is only good for one year, so it must be renewed every year.

The Statement of Compliance is a document in which you declare, under your own responsibility, that you meet all legal requirements (such as certificate of seaworthiness, insurance, and any necessary boating licenses). You must specify the reservoirs or sections of river you intend to use (you can select all navigable areas) and indicate whether you plan to navigate year-round or only during certain months. The application period opens twelve months before and closes two months before your intended start date. It’s important to be aware of this. So, for example, if you plan to start navigating in June, you need to apply in March.

Once you complete the Statement of Compliance, you’ll need to submit it electronically on the Government’s Electronic Site. If your Statement of Compliance is approved, you’ll receive a letter instructing you to pay the fees (which depend on the length of the boat and the engine power). Once the fees are paid, you’re authorised to set sail.

If this is your first Statement of Compliance, you’ll be assigned a registration number in CHT-00000 format, which must be affixed to the right side of your boat (check the exact size requirements on the Statement).

There are two important points to bear in mind. The first is that you must always have the Statement of Compliance and proof of payment of the fees on board with you when navigating. A digital copy on your mobile phone is acceptable. The second is that if you have previously sailed on a different river basin, you must take your boat to a disinfection station before launching it on the Tagus river basin. This helps to control the spread of invasive exotic species from other basins.

David Pérez Chaparro

Panthos

Visit more posts of the Blog

How to Navigate the Reservoirs of Cáceres

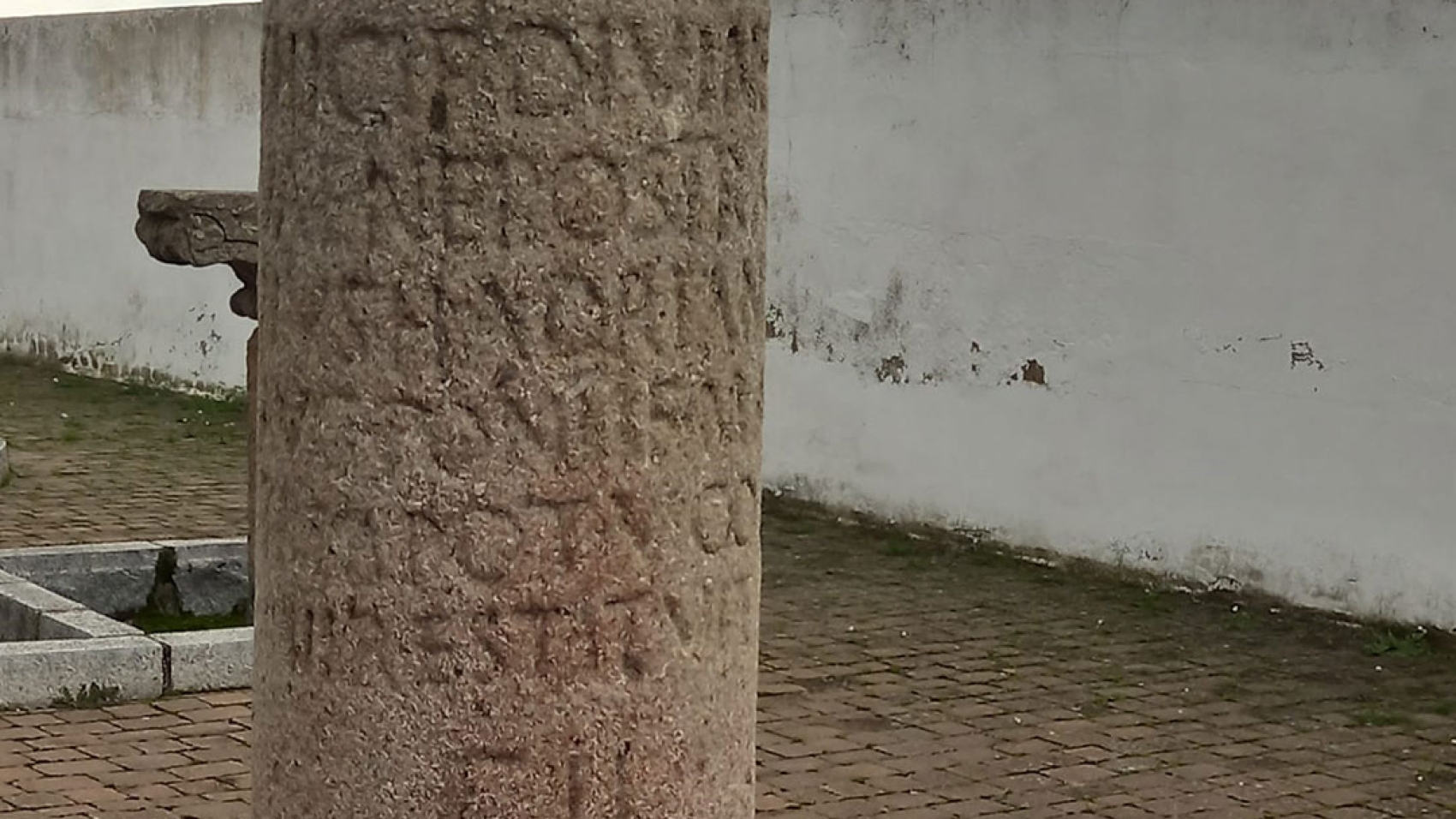

The Vía de la Plata Roman Road through the Caparra Mountains

Perez Comendador-Leroux Museum

Diverse Birdlife in Ambroz-Cáparra

The Vía de la Plata Roman Road through Ambroz-Cáparra